Lieutenant Edwin Alfred Trendell, MC and Bar, MM, MiD – KIA 4 November 1917

By LCol (ret) Tom Compton, CD, BA

Director, Argyll Regimental Museum & Archives

The Argyll Museum and Archives has been very fortunate to receive correspondence from family members of Lt Trendell through Dr. David Campbell and Dr. Robert Fraser. The personal recollections of Lt Percy Trendell, 38th Bn, brother of Edwin, and that of Lt Joe O’Neill 19th Bn, greatly assisted in telling the story of Lt Edwin Trendell.

Edwin Alfred Trendell was born in Lambeth, London, England, on 13 April 1896. He was working as a “student, dairyman” when he joined the 19th Battalion on 11 November 1914 in Toronto. Edwin was single and 18 years, 8 months old at the time.

Trendell arrived in France with the rest of the 19th Bn, on 14 September 1915. The 19th soon moved forward into the line to relieve other units, and at Mount Saint Eloi, April 1916, Private Trendell was Mentioned in Despatches for carrying critical messages under fire. He was soon recognized for his leadership ability, being appointed Acting Lance Corporal on 24 April 1916, and then promoted Corporal and appointed Acting Lance Sergeant the same day, 30 April 1916.

Trench Raid

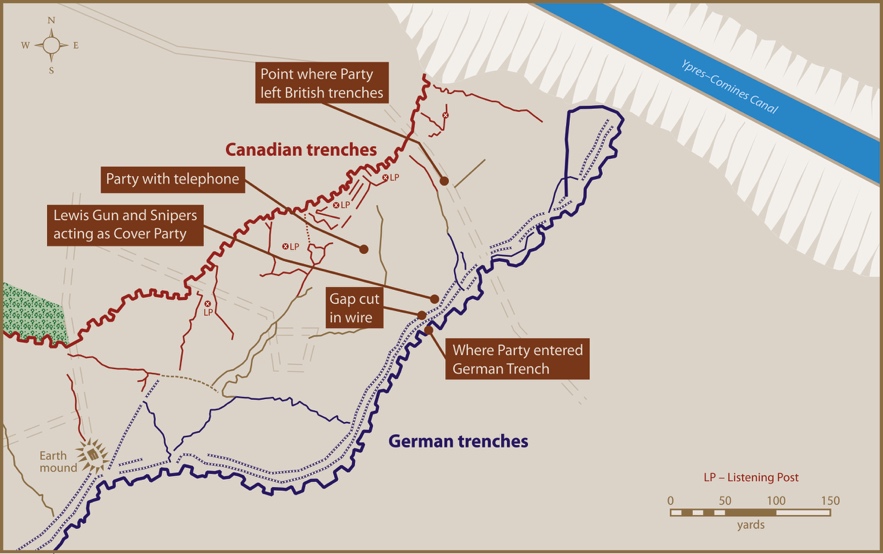

Later at Palingbeek, Belgium, Sergeant Trendell was involved in the daylight trench raid on 29 July 1916. In this action, Trendell was part of the firm base for the raid. The group was forward of the Canadian trenches, maintaining a critical point from which the assault group went forward to enter the German trenches and cause havoc. From his vantage point, the firm base could observe the assault group’s approach, provide cover fire from small arms, direct artillery support with the attached forward observation officer, and maintain a direct link by telephone lines to the rear. This position became vital as the assault group withdrew through the firm base. Capt Kilmer, the leader of the assault group, was seriously wounded during the extraction. After the Canadians shot up and chucked grenades into the German trenches, the enemy responded with ferocious machine gun and artillery fire. Capt Kilmer was extracted with the help of two soldiers, Privates Joseph Newton and Wilfred Wilson. The two privates had found Capt Kilmer face down and unconscious in a shell hole:

“Seeing that Kilmer’s ankle and leg were badly injured, Wilson very gently tried to pick up the officer, who suddenly revived and implored his rescuers to ‘hurry up.’ Wilson replied, “I’m afraid of hurting your leg sir.” But Kilmer insisted that all three of them get a move on, hissing, “Damn the leg, get the rest of me in.” As Newton explained, “We each took an arm and dragged him back to the ditch. Here we were met by Sergt Trendell, L/Cpl Dinsmore and Pte Livingstone, who brought Capt Kilmer in.”

For his actions during the trench raid, Sgt Trendell was awarded the Military Medal, and in August 1916 he was confirmed in his rank and promoted to Sergeant.

Figure 2. A map of the ground where the trench raid took place. Sgt Trendell and the rest of his group were at the point indicated by “Party with telephone”. (Courtesy of Dr. Mike Bechtold)

Figure 2. A map of the ground where the trench raid took place. Sgt Trendell and the rest of his group were at the point indicated by “Party with telephone”. (Courtesy of Dr. Mike Bechtold)

Vimy

By March 1917, the Canadian Corps was repositioning itself in anticipation of the attack on Vimy Ridge. Numerous raids were conducted by the Canadian Corps during the lead-up to the capture of the ridge, and the 19th Bn was involved in a significant raid on 20 March, involving four officers and 63 other ranks. By now Lt Trendell was recognized for his leadership and commissioned as a junior officer.

From the area of the Canadian trenches near Thelus, the 19th launched its raid into German positions. Lt Trendell may have been part of this raid. The 19th’s troops waited for the initial artillery barrage to lift 100 yards. At 4:58 a.m. the signal was given to move, and the Canadians leapt into the German trenches. A comprehensive assault to the right and left of the entry point saw the 19th raiders hurl grenades and mortar bombs into dugouts and trenches as they fired and manoeuvred through the trench systems. The signal to withdraw was given at 5:13 a.m., and the Canadians scrambled back to their lines.

The Commanding Officer, Lt Col Lionel Millen, was “overjoyed with the results of the operation. In just over fifteen minutes, the raiders had destroyed a number of dugouts with their occupants, captured five unwounded prisoners, and identified the unit facing them – the 263rd Reserve Infantry Regiment. Moreover, the cost in casualties, for the number of men involved, had been remarkably small. Three other ranks … [wounded].”

While the records are somewhat incomplete, it is known that Trendell was awarded a Military Cross for actions during this period. The trench raid was the most significant action undertaken by the 19th prior to the attack on Vimy, suggesting that Trendell may have distinguished himself at that time. Alternately, he may have been awarded the MC in the lead-up to the attack as part of the Canadian efforts to define the German opposing forces and their layout. His citation reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. At great personal risk he carried out numerous difficult reconnaissance’s, and on one occasion, made a complete patrol of the enemy fire, gaining information of great importance.”

Less than a month later, the Canadian Corps attacked Vimy Ridge and Lt Trendell was assigned the task of establishing a reporting centre in order to relay information to the rear as the 19th advanced to its objectives. During the attack, 9 April 1917, Trendell received either shrapnel or gunshot wounds to each shoulder; both are stated in his records. The citation for the award of his second Military Cross reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. Although twice wounded, he continued on, and established a reporting centre. It was due to his determination and courage that much early and valuable information was sent back.”

Lt Trendell remained in hospital until 15 May, when he was discharged and returned to the 19th Bn.

Passchendaele

In early November 1917, the 19th found itself in the line outside of Passchendaele. The battle was notorious for the obscene conditions that men and horses had to live and fight through. The terrain was inundated with water from the destruction of the careful drainage system used by local farmers. Heavy shelling by both sides had obliterated any means to remove the water, and the stench of decaying men, animals, and the offal of war added to the sickening atmosphere. By this time, Lt Trendell was appointed the battalion Scout officer. A 19th Bn officer, Lt Joe O’Neill, paid tribute to the remarkable audacity of Trendell and his scouts at Passchendaele. Many years after the war, he recounted:

“The 19th Battalion was always very proud of their scout section and we had great reason to be proud of that section, because they had done some marvelous work. Well up in Passchendaele the officer was, his name was Trendell and the scout sergeant was Barney Glendening [sic]. Well they crawled into what was our company headquarters this night … our company headquarters by the way had been a house but the whole house was down. We had a tunnel dug underneath the wall and it came up in the corner of this cellar. They crawled in there and there was very heavy shelling going on, and after we had chatted awhile about odds and ends, Trendell said ‘That Passchendaele village up there isn’t nearly as badly battered around as I thought it was.’ Somebody said ‘You thought, how do you know?’ This was before Passchendaele was taken. Oh he said, ‘Barney and I were up there, why sure we went across through the German line. We got up into Passchendaele village and we even got back in and back a piece and we went into one of the German cook-houses, and here do you want some German sausage?’ They had stole the German sausage out of the German cook house and fed us, and of course we naturally had a laugh, we said, ‘What did you do then?’ ‘Oh we had a funny little thing happen,’ he said, ‘Barney and I thought we’d go back country and see what it looked like back there. They said there was a trench up there, and we were going down this German trench and we met about twenty Huns coming up, a working party coming up, well all we could do was squeeze over to the side of the trench and pull the Harris hats and they said Good-nok, and we said Good-nok [sic] and the whole bunch passed us and by that time we thought we better get out.’ They came home. Now it just happened that on the road home, they ran into a German machine gun nest. They found this German machine gun so they figured they’d take it, go out the next night and explore it and go over and take it. So the next night they did go over, the two of them, trying to figure out how they’d take it just the two naturally, the rest were left behind. Well while they were out there, the Germans decided to put on an attack, and they dropped their S.O.S. barrage on our line. Of course our people shot up the S.O.S. it was the battalion next to us, it wasn’t our battalion… and there they were caught between the two barrages. Well as they tried to rush back somebody in this other battalion mistook Trendell for a German and shot him, they thought he was a German. But Glendening, he got back all right, and Glendening was living in Toronto until recently. About a year ago he died…” (From David Campbell, _It Can’t Last Forever; see Sources.)

The death records with official circumstances have been lost, so we only have the testimony of Joe O’Neill as to how Lt Trendell died. The remarkable service – including two Military Crosses, a Military Medal, and being Mentioned in Despatches – of Edwin Alfred Trendell had come to an end, 4 November 1917, in the mud of Passchendaele. Lt Trendell is buried in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery, Belgium. On his grave marker, his family added the inscription, THE SOULS OF THE RIGHTEOUS ARE IN THE HANDS OF GOD.

Sources

David Campbell, It Can’t Last Forever: The 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War, provided the majority of the details herein.

Library and Archives Canada, Personnel Records of the First World War.

Joe O’Neill transcript sourced from Library and Archives Canada, RG 41, B-III-1, Records of the CBC, Flanders Fields, Vol. 10, 19th Battalion, Transcript of interview with Joe O’Neill, Tape 3, pp. 1-2. Quoted from draft material of It Can’t Last Forever: the 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War by David Campbell.

Correspondence, maps, and images as cited.

Notes

From the personal diary of Lt Percival (Percy) Charles Trendell, 38th Bn CEF, brother of Edwin Alfred Trendell, forwarded by Percy’s great-grandson, Matt Warburton, in personal correspondence with Robert Fraser, 13 Nov. 2017.

THAT NIGHT OF 5TH NOVEMBER WE WERE ASLEEP ON THE STRAW when I was awakened by a runner with a flashlight and piece of paper. He handed them to me. It was the message from C.O. 19th Bn – I have it yet, on the field message form as received by our signaller – to the effect that Edd had been killed on the night of the 4th November and requested that I be allowed to go to the 19th, presently at St. Lawrence Camp, Vandhoek, (near Ypres), for the funeral. I must say that I had never heard of a funeral before for anyone killed, except as might be carried out by the battalion padre. They must have thought a lot of Eddie. But then he was an original 19th man. Had gained his commission and had the M.M., the M.C, and had won his bar to his M.C. at the Vimy attack.

It was a cruel blow, but I will not dwell on it. He was pure gold - as his commanding officer Col. Millen was afterwards to tell me.

In a daze I got my permit and moved out to the main road north and picked up a lorry towards Ypres. The driver knew St. Lawrence camp, it was a mere site in a field with camouflaged tents out of shell range behind Ypres.

They put me in a hut with the 19th Scout section - his section, and the adjutant told me his body had been brought out and was in a rough box made especially by the pioneer section of the 19th. He told me Eddie had gone forward with his scouts to lay tapes that night for an attack of the btn in the morning hours. His [S]gt told me that Edd usually led the section in all forward work but this time he asked the [S]gt to lead and he followed him. A burst of machine gun fire caught the section in no-mans land. Edd was the only casualty and he was shot through the back of the head. It was instantaneous of course. It was remarkable that they were able to drag him back.

The adjutant said I would probably want to remember him as he was and I agreed that I should not ask for the box to be opened. I have often wondered if I should have seen him - but perhaps the older man knew best.

The following morning, in a steady drizzle we laid him in the trench in the Prison Cemetery as it was then called. It was located in a field immediately behind the old prison at Ypres. Edd had written to me shortly before, and in a remarkable letter he said that the trip now coming into Passchendaele would in all likelihood be his last with the unit, as he had been warned of appointment as Brigade Intelligence Officer. But he had said he had premonition that he would not get through this time, and he would like to be buried at the White Chateau. This was a very well known forward position at Ypres where so many men had been lost. The adjutant told me that the authorities were no longer permitting burial at the Chateau, and that in the long run it would be better because all bodies would eventually have to be moved to designated cemeteries.

And so it was, and the cemetery is now, and has always, been beautifully kept. I visited it on several occasions in later years. On the way back to camp by the western Gate, we crossed the railway tracks at the old ruins of Ypres station and the Germans were shelling the point. A red cross train stood on the tracks. That was pretty far forward to have a rail-head for the hospital train.”

From personal correspondence in which Dr. David Campbell responds to Matt Warburton (great-nephew of Lt E.A. Trendell), copying Dr. Robert Fraser, 15 Nov. 2017.

“Sadly, I think friendly fire from artillery, rifle, and MG fire was probably common enough on both sides of the Western Front that few, at that time, would have ascribed the same weight to it as most people today would.”

“I’m afraid I can neither confirm nor refute O’Neil’s claim that it was friendly fire that killed Lt Trendell, but given the circumstances in No Man’s Land at that time and the quality of O’Neill’s testimony in other contexts, I thought it reasonable to include. Let me explain:

I checked other sources and did not find anything to refute what O’Neil claimed. Nor am I aware of any special procedures involving incidents of alleged friendly fire. Casualties, especially from one’s own artillery, were regularly noted in official and private records. I have never come across any official statistics indicating what percentage or even average number of Canadian casualties may have resulted from friendly fire. It was not a situation that would have touched off the degrees of investigation and assignment of responsibility that would occur in a similar incident today. With both sides shooting at each other across No Man’s Land, I’m sure that even if an official inquiry had been initiated, it likely would not have turned up anything conclusive.

O’Neil’s account came in a recollection many years later but, at a time, when there were still many 19th veterans. As far as I know, no one took exception to it. He was, like Lt Trendell, an excellent officer, well-respected, well-liked, and an active member of the 19th Battalion Association after the war. He was one of the initiators of a project to plant trees in a cemetery near Mons, where a number of 19th soldiers were buried at the end of the war. In other words, I considered O’Neil a reliable source and, to repeat, I have not discovered any evidence to refute it.

I don’t think there was any conscious effort to deceive or cover anything up in Trendell’s case. Even if O’Neil and others in the battalion were certain that the gunfire that killed Lt Trendell came from the Allied side of the lines, that conclusion may not have made it into the official records. O’Neil’s account remains entirely plausible, if difficult (or even impossible) to verify.”

CWM, 19740071-017 58C 1 1.9, untitled file of correspondence and notes regarding 19th Battalion history, typed reminiscences of Father Ewen J. Macdonald.

Perhaps nobody in the battalion felt Trendell’s loss more keenly than his devoted batman, Brown. According to the battalion chaplain, Father Ewen Macdonald:

“Trendal [sic] was on scout duty and was killed in no man’s land. Brown, an old English soldier, was his orderly. Often before, I had watched this faithful man, no longer able to do heavy duties, come in, early in the morning, to see that his friend was well covered or to get his officer’s kit arranged. I saw him that day carry in the dead body. That alone was heroic, considering the distance and the ground. With moisture dimmed eyes, I watched in silence. He laid him down at my feet. He stood to attention, saluted gravely and said ‘I don’t care what happens now.’ He sat down outside the pill-box, a most dejected looking man with tears streaming. I went to console him and found that he had a nasty carbuncle on his finger. I asked him if it hurt. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but I loved that boy and I didn’t want to report it, in case they might send me out of the line.’ I returned to the Doc and using my ‘pull’ with Joe said ‘Doc, that old Englishman has a decent ‘Blighty’, send him out.’ The doctor came over, examined the sore, put on the usual bandage and gave him that ‘Blighty’ ticket which would let [him] pass along with the other walking wounded. We stood and watched the old man go. Suddenly he turned from the duck-boards, through the mud, to a pill-box a hundred yards or so to our left. I remarked that the ‘old boy’ had become youthful again. His words ‘I don’t care what happens now’ were still fresh in my memory. He leaned over the little entry into that German miniature fort, which now, of course, faced our way. He was saying good-bye to some friend among the scouts who had their headquarters there. It seems he said ‘boys I got a Blighty.’ They were the last words he ever spoke. A shell landed under him and killed him instantly. There was a box of German flares nearby. The flares ignited. The doctor ran over and I followed. One of the men we pulled out is now head of the 19th Bn. Legion in Toronto. Old Brown is buried with the officer he loved. So it is and much suchlike, when there is war.”

Figure 1: Lt Edwin Alfred Trendell, KIA 4 November 1917.

Figure 1: Lt Edwin Alfred Trendell, KIA 4 November 1917.

Figure 3: A newspaper announcement about Trendell’s being wounded. Source: Toronto Telegram, April 1917.

Figure 3: A newspaper announcement about Trendell’s being wounded. Source: Toronto Telegram, April 1917.

Figure 4: A carrying party traverses duckboards across the morass of the Passchendaele battlefield. The horror of the sodden terrain is evident. Thousands of men and horses were lost slipping into the liquid mud. Source: Canadian War Museum through Dr David Campbell.

Figure 4: A carrying party traverses duckboards across the morass of the Passchendaele battlefield. The horror of the sodden terrain is evident. Thousands of men and horses were lost slipping into the liquid mud. Source: Canadian War Museum through Dr David Campbell.

Figure 5: Lt Trendell’s grave marker in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery, Belgium. Source: Findagrave.com.

Figure 5: Lt Trendell’s grave marker in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery, Belgium. Source: Findagrave.com.

Figure 6: The Canadian monument in the village of Passchendaele, Belgium. The inscription reads: “The Canadian Corps in Oct–Nov 1917 advanced across this valley, then a treacherous morass – captured and held the Passchendaele Ridge.” Author’s collection.

Figure 6: The Canadian monument in the village of Passchendaele, Belgium. The inscription reads: “The Canadian Corps in Oct–Nov 1917 advanced across this valley, then a treacherous morass – captured and held the Passchendaele Ridge.” Author’s collection.

Figure 7: An example of the Military Medal similar to that awarded to Sgt Trendell for his actions during the 29 July 1916 trench raid. Image source, Wikipedia.

Figure 7: An example of the Military Medal similar to that awarded to Sgt Trendell for his actions during the 29 July 1916 trench raid. Image source, Wikipedia.

Figure 8: An example of the Military Cross awarded to Lt Trendell twice. The first was possibly as a result of his actions during a trench raid 20 March 1917 or before the attack on Vimy; records are incomplete. The second was as a result of his actions during the battle of Vimy Ridge. Image source, Wikipedia.

Figure 8: An example of the Military Cross awarded to Lt Trendell twice. The first was possibly as a result of his actions during a trench raid 20 March 1917 or before the attack on Vimy; records are incomplete. The second was as a result of his actions during the battle of Vimy Ridge. Image source, Wikipedia.