LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr (B 116254) (1916-45)

Introduction

One of the planning notes for the November 2020 commemoration was to move the story chronologically from the early days of action in late July/early August 1944 through to the end in early May 1945. It is always a sobering effort to review lists of Argylls killed in action. After the cold and misery of Kapelsche Veer in late January 1945, the battalion moved into Germany and the battle of the Hochwald Gap in late February 1945. Capt Norm Donaldson was wounded on 26 February (his third wound of the war) and died from it. I knew Norm’s life well, thanks to Helen Donaldson, his wife, who provided me with his wartime letters; shared her memories; and did an interview with one member of the Black yesterdays staff. Their story is well told in the book.

I moved on to the next name on the list, LCpl Frederick Woodward, and pondered it. My first stop was the Canadian Virtual War Memorial. Often projects related to the memory of wartime casualities (Operation Picture Me) or family members will post images. There, I gazed on the broad, gentle smile of LCpl Woodward and he intrigued me. In due course, I spoke with one of his two daughters, Carol Burak, who agreed to an interview. Seventy-five years later, the memories retain their power and their hold. I asked her if there was one word that characterized her loving father. Without hesitation, she said, “gentle”; she then immediately added a qualifying word, “very.” As Lt Alan Earp often remarks about Argylls with whom he served, he was another “good and gentle man.” As always, I appreciate the assistance of Argyll families who share their memories and their loss. Carol also gave permission to use the many images she has posted to the family tree on Ancestry.ca. Thank you, Carol.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr (B 116254) (1916–45)

Wounded 26 February 1945; died of wounds 21 April 1945

“chummed around for two weeks, and stayed in touch forever”

Immigration is one of the constant threads in the fabric of Canadian history. The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed some of the largest increases as some regions of Canada industrialized while others opened up to new agricultural settlement. Frederick Woodward Jr and Margaret Sedge were Canadian-born children of English immigrants in one of the country’s two largest and fastest-growing cities.

Frederick Woodward Jr was born in Toronto on 28 January 1916 to Frederick Woodward Sr (1889-1965) and Blanche Hibbert (1889-1977). Fred Sr immigrated to Canada in 1910 from Lancashire, England, with his brother; he married Blanche in Amherst, Nova Scotia, in 1911; by 1913, they were in Toronto. Canada declared war in August 1914 and Fred Sr enlisted the following year; his older brother, Walter Henry Woodward (1887-1915), had also enlisted and was killed at Ypres in October 1915. Fred Sr went overseas in February 1916, less than a month after Fred Jr’s birth. He was wounded at the battle of the Somme, returned to Toronto in December 1918, and was discharged the following month.

Fred Jr had three siblings, all girls, and he was the second eldest. He attended school locally and completed grade 8 before going to work at the age of 13. He worked first as a baker at the Scotch Bakery in Toronto and later as a milkman, or “dairy salesman,” delivering his goods with a horse-drawn carriage. According to his daughter Carol, in July 1934 he met Margaret Sedge (1918-2013) at Thurstonia Park in Sturgeon Lake, where the two families vacationed; Marg was with her parents and her sister. As teenagers, “they … met at the swings, and he played mouth organ.” They “chummed around for two weeks, and stayed in touch forever.” The young couple married in Toronto on 6 February 1937; he was Baptist, she belonged to the United Church. At the time of their marriage, Marg was a bookkeeper in Toronto; her father, Frederick Walter Sedge (1889-1941), was born in England. Fred and Marg rented a house at 9 Roblock Avenue in Toronto and started their family; their daughter Laurette was born on 29 October 1937; Carol Anne was born on 20 April 1939.

“little things”

Fred and Marg Woodward’s lives were tranquil and happy. They had two delightful daughters, a rented family home that his daughter remembers fondly, and extended family all nearby: his parents lived at 17 Pryor Avenue with his youngest sister, Dorothy Blanche; his other sisters, Emily and Hilda, were both married and also lived in Toronto. He had a job, which he liked, often came home for lunch, parking his horse and wagon outside, and took his daughters to “the barn at Finlay Dairy to visit his horse.” Daughter Carol Ann remembers the “little things” and they are all good.

“Don’t tell Mom”

Few Canadian families were unaffected by the war. Fred’s enlistment in Toronto on 8 September 1943 changed the course of life for this family forever. A “bread salesman” at the “Scotch Bakery” in Toronto and a member of the A.F.of L. Local 647, he had, according to his personnel file, made no arrangements for the post-war. Simply put, he planned to “Return to Dairy Salesman.” He was 5’, 9 1/2” with blue eyes and dark brown hair; he weighed 136 lb. Even in his early days of training, the Woodwards retained a semblance of familial normalcy. He returned home to Toronto as often as he could. “I remember little things,” daughter Carol Ann said. “We would meet him at the train, Mom would doll us up.” There were special treats for his daughters; one time, he “took us to a soda fountain,” admonishing them on the way home “Don’t tell Mom.”

Fred’s initial training was in Toronto, before his posting to No.25 Basic Training Camp in Simcoe on 7 October 1943, where he remained until his transfer on 7 December to the training camp at Ipperwash. Granted Christmas leave, he went home on 24 December 1943. Pte Woodward attended the “Methods of Coaching” rifle course in February 1944, attaining his qualification. He had a furlough from 24 March to 6 April 1944 and returned again to his family in Toronto. He was promoted acting lance corporal on 10 April 1944. Granted another furlough from 3 to 14 June 1944, Pte Woodward returned home, yet again, to his waiting wife and daughters. He became acting corporal on 11 August. With overseas deployment on the immediate horizon, he received embarkation leave from 8 to 18 September. For reasons unknown, he relinquished his appointment as acting corporal and reverted to private on 9 September 1944. Pte Woodward embarked in Canada on 4 October 1944, disembarked in the United Kingdom on the 11th, and reported for duty two days later as part of 2 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit, which was “redesignated” to 2 Canadian Infantry Training Regiment (CITR). He went from the CITR to the X-4 (undesignated reinforcements list) and on to the continent. The issue of reinforcements was critical to infantry regiments such as the Argylls, which had been badly depleted by battle since July (see Pte Alexander Nickoloff). The Argylls, stationed near Drunen, took him on strength on 22 November 1944.

“even war can at times have its pleasant aspects”

The battalion moved on 25 November to “a monstrously large seminary which was to be our home for the next few weeks,” near “the little town” of Stokhoek. The unit was “united for the first time since leaving England” and ready for its “rest period.” They were awakened the next morning by “the cheery playing of the Argyll Pipe Band” and the troops could “spend their first day devoid of any worries about patrols, ‘Moaning Minnies,’ snipers, and other unpleasant aspects of modern warfare, which had been their constant companion for four dreary months.” The rest of their day was devoted to church services, movies, writing letters, and “personal clean-ups.” The battalion discovered an abandoned German rifle range nearby and set up a training program for the companies as well as a “School of Instruction for NCOs” to give them “a firmer practical basis for the practical work lying ahead.” The days ahead continued with parades, inspections, more training, movies, and “a fairly large quantity of beer was purchased for the Men’s Wet Canteen.” By the 28th, Christmas parcels started to arrive along with the return of Lt-Col Dave Stewart, the unit’s beloved commanding officer. There were also sports “on an extensive scale, entertainment provide “mostly through” the Salvation Army, concerts, and inspections. Lt Bissell, the unit’s war diarist, opined that “the Battalion … went to be justifiably feeling that even war can at times have its pleasant aspects.”

“a hard-hitting, efficient fighting team”

Pte Woodward’s introduction to the battalion came at a unique time. It was out of the line and with no prospects of an immediate return to it. As Bissell put it, “the current rest period was a veritable god-send, enabling the C.O. and his staff to instill a new ‘ésprit [sic] de corps’ into the men and thereby once again make the Argylls into a hard-hitting, efficient fighting team.” Pte Woodward was a designated part of that team. Maj R.D. “Pete” MacKenzie took over D Coy on 2 December and the next day the battalion, much to everyone’s surprise, moved back to Drunen. The unit, as a whole, was no longer together and the companies moved back to their positions along the swollen Maas River. The Argylls began patrolling, and on the 5th a small patrol from C Coy had a brief fire-fight with the enemy. Pte Alex Eli Laba died the next day. That day (6 December), Maj MacKenzie, D Coy, promoted Pte Woodward to lance corporal.

“the little pleasures”

The days were cold and clear, or cold and wet; occasionally, there was sun while enemy shelling, mortars, or artillery were frequent. There were still “the little pleasures” – bath parades, movies, and the Sally Anne Teawagon” – that helped “substantially in making warfare bearable.” On 21 December, the battalion moved back to Stokhoek. Argylls hoped for a “quiet” Christmas but were on a two-hour notice to move if the Germans broke through the Ardennes. Battalion headquarters was located in several pubs and civilian buildings while the companies were “all located on a side road.” There was “great satisfaction … that the otherwise commonplace little village could boast of … running water and electric light.” Christmas dawned “bitter cold and crystal clear.” The commonplace toast was that “all be united with our families and friends on Christmas Day 1945.” There was a proper and “delicious” turkey dinner at noon as well as cigars, cigarettes, and a parcel for every Argyll “courtesy of” the Argyll Women’s Auxiliary. By the end of the month, D Coy were “in houses of sorts but very uncomfortable” near Dorst. On the 31st, the unit moved to Rijen except D Coy, which remained in Gilze, where the old year came and went. Mail delivery – a vital link with home for soldiers – had “bogged down.” By 9 January 1945, the Argylls were in Waalwijk. Two days later, they received word of attacks by the Allied tactical air force on the German stronghold at Kapelsche Veer. Its presence loomed larger in the battalion’s consciousness as the days passed. The weather turned colder, there was a snowstorm, the Maas River rose, and there were fighting patrols that resulted in casualties.

Kapelsche Veer – “the grim unreality of it all”

The failure of the Lincoln & Welland Regiment at Kapelsche Veer brought the Argylls into the fight. It also entailed the loss of Lt-Col Stewart, who refused to launch an unsupported attack. The Lincs suffered heavily on 26 January 1945. A Coy moved onto the dyke on the 27th; D Coy relieved them the following day. The policy of relief was deliberate for two reasons: the biting cold and making it “possible for all the new reinforcements … to get accustomed to being under fire.” By 1300 hours, D Coy was on its position and under heavy mortar fire. The Germans counter-attacked at 2200 hours, driving back the Lincs and D Coy. It fell back, dug in, and was in turn relieved at midnight by B Coy. The Argylls suffered 1 KIA and 15 wounded. The “approaches to the two demolished houses” on the dyke “were perfect ‘killing ground’ for the enemy,” as D Coy had learned. On the 29th, C Coy had its day on the dyke’s “grim unreality,” as Pte Robert Mason of C put it (see Pte Donald Douglas MacKeracher), “a nightmare.” By the 30th, it was over. On 31 January, the Argylls spent the day “in clearing the battle field of the debris of battle” in “surprisingly warm” weather. At Kapelsche Veer, the Argylls rotated their companies on the dyke. It was a deliberate plan intended to give new reinforcements some sense of “being under fire.” LCpl Woodward now knew what it was like and the experience awaited the most recent reinforcements. For some reinforcements, however, they had, as the war diary expressed it, “frightened themselves into the belief that they would rather face a Field General Court Martial than the enemy.” There were only a “few cases of ‘cowardice in the face of the enemy’” and they were charged.

“fieldcraft and ‘fire and movement’”

The early days of February were mild, then “dull and wet,” with a rigorous training program set up by the new CO, Lt-Col Fred Wigle. There were new reinforcements and ranges. D Coy and LCpl Woodward were on the ranges on 7 February and received instruction in “fieldcraft and ‘fire and movement.’” There was a company dance that night. There were patrols, a buzz-bomb (V-1 rocket) that hit Waalwijk, and a move to Elshout on the 10th and the old positions along the Maas. D Coy was in Heusden. Its fighting recce patrol on the 18th did not encounter the enemy; later that day, the battalion moved to Loon op Zand and then to Boxtel on the 20th. Once again, the Argylls were on notice to move for the coming battle. At 0230 hours on the 23rd, they entered Germany with a single piper at the head of the long column. “Morale and optimism were high,” wrote the war diarist; it was the “moment that we had waited, hoped and struggled for …” LCpl Woodward, in the same manner as the other reinforcements who survived the dyke, may not have been “accustomed to being under fire,” but he now “knew what it was.” Plans were set for OP Blockbuster with H-hour at 0430 hours on the 26th. “Snuff” force, one of the divisional battle groups, which included C and D Coys, left at 1800 hours on the 25th.

“mortar and machine gun fire were intense”

Because of rain the previous day and soft ground, tanks were “not as much help … as had been originally hoped.” Overcast skies and poor visibility resulted in “lagging” air support. During the morning of the 26th “Snuff” force, which included C and D Coys of the Argylls, “encountered,” as Maj Hugh Maclean wrote in 1945 at the end of hostilities, “great difficulties in getting forward; mortar and machine gun fire were intense.” By mid-afternoon, they reached their objective. The unit war diarist considered the day “successful and casualties were comparatively light”; he had previously noticed that enemy fire, which had “pinned down” C and D for most of the morning, was “heavy. D Coy sustained most of the day’s casualties. [Note: This assessment is by no means conclusive. I am in the process of identifying the casualties by company and, so far, they are mainly in D.] LCpl Woodward was one of those in D Coy wounded on 26 February 1945. Lt Bill Shields, one of D Coy’s platoon commanders, remembered “the stuff was flying around a bit.” He was “running like hell” with his batman and a corporal; one was hit in the knee, the other “badly wounded” in the groin. They made it to a hedgerow, fired back, dislodging the Germans “from this bloody building,” and “hit one or two of them with the Bren …” D Coy was in close proximity to C because Shields saw Capt Norm Donaldson “lying there.”

“dangerously ill”

The Argyll medical officer, Capt Doug Bryce, characterized the Regimental Aid Post (RAP) and his “management of wounds “as “essentially massive first aid [and] the use of blood and plasma where indicated.” “In most cases,” he observed, “the medication … of the greatest use for seriously ill patients was intravenous morphine, of which we had a good supply.” On the 27th, Padre Charlie Maclean told Adjutant Claude Bissell that there were “many with serious mortar wounds,” such as Capt Norm Donaldson of C Coy; he was taken to another unit’s clearing station, which was closer than the Argyll RAP. As for LCpl Woodward, he had “G.S.W. (Machine Gun) through left hip, pelvis and rectum.” The wounds were catastrophic. His first operations came 36 hours later at 7 Canadian Field Surgical Unit. The medical officer was the distinguished surgeon Lt-Col Arthur Turner Bazin, DSO (1872-1958). Woodward had a “left inguinal colostomy and cystotomy done” and his “hip joint laid open and packed.”

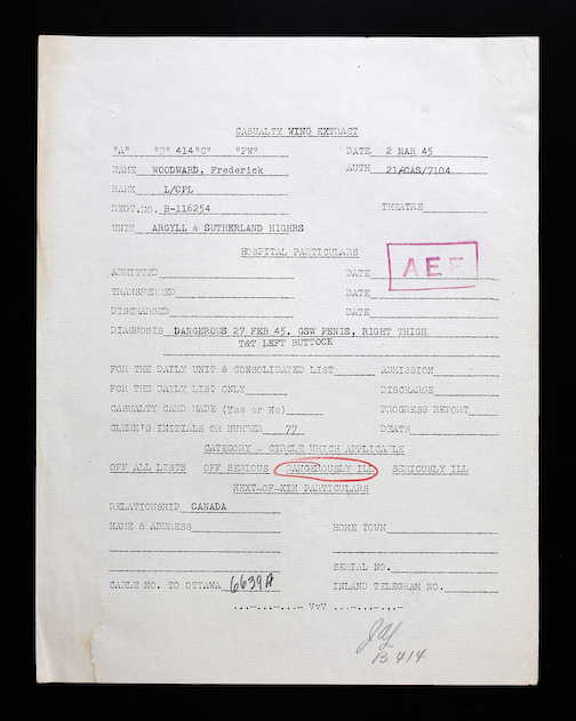

Casualty wing extract for LCpl Woodward.

Casualty wing extract for LCpl Woodward.

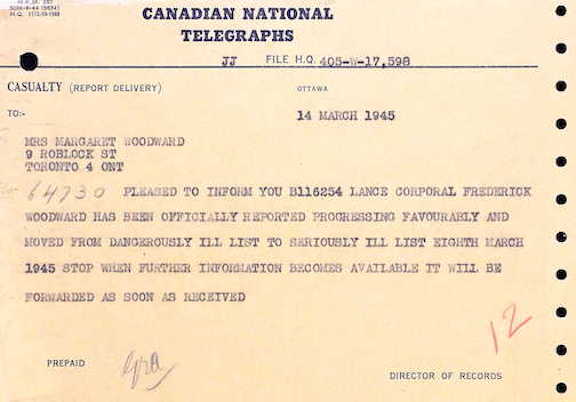

Telegram 14 March 1945, advising that LCpl Woodward was “reported progressing favourably.”

Telegram 14 March 1945, advising that LCpl Woodward was “reported progressing favourably.”

“gradually slipped backwards and died 21 Apr 45”

On 2 March, LCpl Woodward’s casualty wing extract read “dangerously ill,” with a gunshot wound to his penis, right thigh, and “T&T” [through and through] left buttock. Three days later, the acting director of records sent a letter to Margaret Woodward advising her of the full scope of his wounds. Doubtless a telegram of 14 March that he was “progressing favourably” and moved from “dangerously ill to seriously ill” gave room for hope. There was little to be done save further operations and the removal of infected tissue. 17 Canadian General Hospital admitted LCpl Woodward on 29 March 1945. His “general condition was poor” and there was further removal of dead tissue. There were more operations on 6 April and his “wounds cleaned up.” Moreover, he “is unable to absorb from intestine.” He “gradually slipped backwards and died 21 Apr 45.”

“pretty horrific injury”

Capt Caleb Zavitz, MD, a vascular surgeon and serving Argyll officer, reviewed LCpl Woodward’s medical condition in late October 2020 and offered this assessment:

“Unfortunately this lad had a pretty horrific injury, which took out his hip and most of the contents of the pelvis. Today we’d struggle with wounds like his, but at the time, the best they could do was progressively remove whatever was too damaged or diseased to heal over the course of weeks and months. Certainly lots of trips to and from the operating room for debridements and reoperations. Eventually malnutrition and complications caught up with him.”

“War is a terrible thing, more terrible to you at home”

After Norm Donaldson’s death on the 26th, Capt Claude Bissell wrote to Helen Donaldson, his wife:

“War is a terrible thing, more terrible to you at home than to us over here, since we are a large group who share our joys and sorrows together and are spared the torments of loneliness.”

“he was the love of her life to the day she died”

Bissell’s words capture the essential truth for the bereaved at home. For the Woodward family, there were two months of unmitigated personal anguish as they confronted the awful news conveyed by telegram and letter. Time has not diminished the remembrance of that loss or its power to bring forth tears. Daughter Carol Ann Burak remembers “sitting at the top of the stairs, an army person comes and he was gone … Mom had hope but knew he couldn’t live.” Fred Woodward wrote home frequently. In hospital, Carol remarked, “he could speak but his body was done, nurses wrote letters for him.” He “watched his body go. Mom said, it’s a blessing. I was only six.” Pte Woodward left little overseas. There were the usual sorts of personal items, two black wallets (one with a photo folder for the pictures of his family), a watch, a gold signet ring, and 64 letters. It is rare to find a number attached to personal letters of those killed in action and, to date, nothing approximating this number. They were all returned to Marg Woodward.

Carol’s mother “grieved to the day she died.” She remarried in 1947 to her best friend’s brother, Carl Eugene Welch (1917-2013), another veteran, and they had two children. “My step-Dad was wonderful,” Carol said, “but he didn’t get all of her. He [Fred] was the love of her life to the day she died.” When her mother was dying in hospital, Carol “whispered in her ear – ‘to go and see Fred’ and she died in five minutes.”

“It is,” she said, “so hard … [it is] crushing”

Carol recalls their home on Roblack Avenue in Toronto: “people had Union Jacks flying to signal someone overseas and we had one.” “It is,” she said, “so hard.” Carol says that she “named my son after him to honor my Dad.” The loss of a beloved father “is crushing!”

Between 31 January and 26 February 1945, 8 Argylls were killed in action and 49 wounded.

“a history bought by blood” – Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Friends of Earl Wardell (another Argyll veteran) donated LCpl Woodward’s poppy with respect for his service and in memory of Earl.

Note: LCpl Woodward’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Carol (Woodward) Burak visiting the grave of her father, LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr, in Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, England.

Carol (Woodward) Burak visiting the grave of her father, LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr, in Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, England.

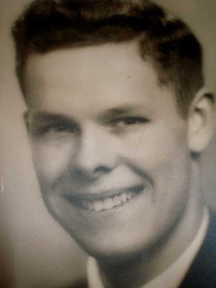

Frederick Woodward Jr.

Frederick Woodward Jr.

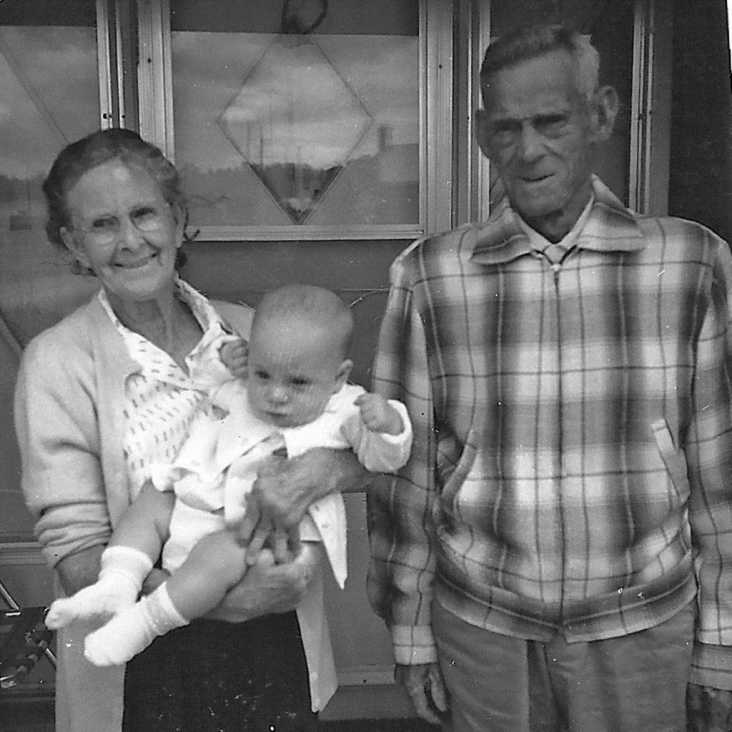

Parents Blanche and Fred Woodward Sr with their great-grandson (Laurette’s son, David Winter), Beamsville, 1965.

Parents Blanche and Fred Woodward Sr with their great-grandson (Laurette’s son, David Winter), Beamsville, 1965.

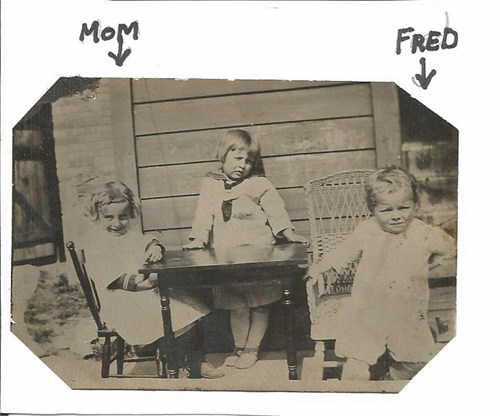

Young Fred Jr with two of his sisters.

Young Fred Jr with two of his sisters.

The Woodward family: Fred and Marg with daughters Laurette and Carol.

The Woodward family: Fred and Marg with daughters Laurette and Carol.

Laurette and Carol at 9 Roblock Avenue, 1942.

Laurette and Carol at 9 Roblock Avenue, 1942.

19 Pryor Avenue, Toronto, the home of Frederick Woodward’s parents.

19 Pryor Avenue, Toronto, the home of Frederick Woodward’s parents.

Fred’s sister Dorothy (“Dot”) with Fred’s daughters, 1942.

Fred’s sister Dorothy (“Dot”) with Fred’s daughters, 1942.

Fred’s sisters Emily and Hilda.

Fred’s sisters Emily and Hilda.

Fred Woodward Sr, Uncle Jack, Laurette, and Carol at Aultsville, 1945.

Fred Woodward Sr, Uncle Jack, Laurette, and Carol at Aultsville, 1945.

Pte Frederick Woodward.

Pte Frederick Woodward.

LCpl Woodward’s daughters, Laurette and Carol – a photo taken in 1944 to send to him overseas.

LCpl Woodward’s daughters, Laurette and Carol – a photo taken in 1944 to send to him overseas.

C Coy digs in with SAR tanks at Kapelsche Veer.

C Coy digs in with SAR tanks at Kapelsche Veer.

15 Platoon reached the top of this hill at Kapelsche Veer, where Lt Perkins threw grenades at the house.

15 Platoon reached the top of this hill at Kapelsche Veer, where Lt Perkins threw grenades at the house.

Sketch of Kapelsche Veer by artillery observers.

Sketch of Kapelsche Veer by artillery observers.

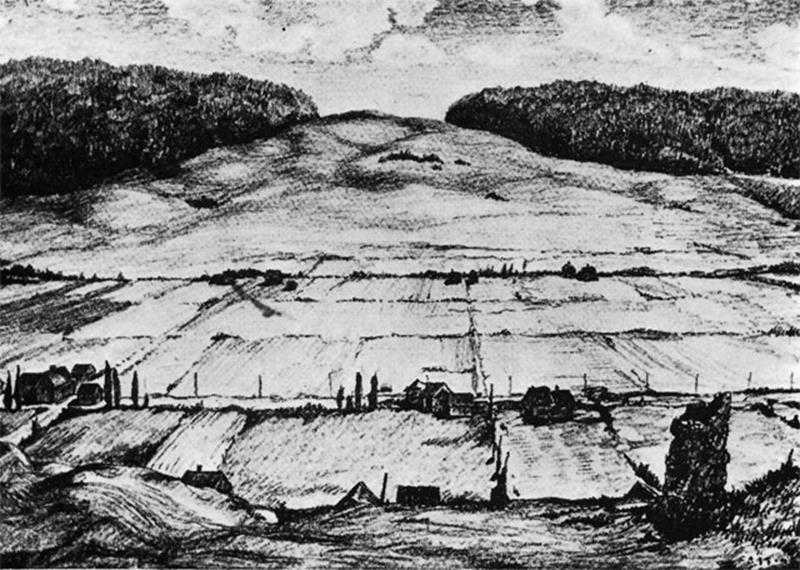

The Hochwald Gap, drawn by Brigadier G.L. Cassidy, DSO, ED, based on sketches made on the spot.

The Hochwald Gap, drawn by Brigadier G.L. Cassidy, DSO, ED, based on sketches made on the spot.

LCpl Woodward’s gravestone, Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, England.

LCpl Woodward’s gravestone, Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, England.