The 19th Battalion Experience at Vimy, 9 April 1917

LCol (ret) Tom Compton, CD, BA

Director, Argyll Regimental Museum & Archives

During January 1917, the British First Army, which included the Canadian Corps, engaged in preparatory work to seize Vimy Ridge. The battle marked the first time that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought together. The Canadian victory at Vimy has been viewed as a milestone in the development of Canadian national identity, and it came about as a result of the staggering work by the entire Canadian Corps, from the lowliest Forestry troops cutting and delivering rough-cut lumber for railroads and bunkers, to the staff officers at brigade, division, and corps headquarters toiling over their sophisticated operational plans and animated by a growing spirit of professionalism.

In the lead-up to the battle, ammunition was dumped in anticipation of the voracious needs of Canadian, British and Australian artillery formations moving into position. Beginning on 20 March, the artillery opened up with 983 guns and heavy mortars, consuming 2,500 tons of ammunition each day. The guns fired to break down the German defences, with a slow drum beat of shelling growing into a thunderous bludgeoning of destructive firepower that included creeping barrages to deceive the Germans into thinking they were being attacked. Preparations also required the construction of reinforced roads and miles of railway to bring the ammunition forward while also allowing for the swift withdrawal of casualties to hospitals. The scale of artillery fire was utterly devastating for the targeted area on and around Vimy Ridge. The Battle of the Somme had seen similar amounts of artillery fire over a long period, but here at Vimy the detailed planning had been refined and a common doctrine for British Army artillery formations was used to coordinate and dominate the battlefield. The Canadian Corps’ counter battery fire, assisted by British and Australian artillery batteries, effectively silenced 83 percent of the German artillery prior to the assault. The result was a hideously heavy weight of fire that the Germans would have assuredly hurled at the Allies given the same chance. The guns targeted German artillery positions, communication nodes, crossroads, known headquarters, and supply dumps, tore gaps in defensive wire entanglements, collapsed trenches and bunkers, and generally rearranged the landscape. German soldiers were left stunned, half crazed and worse: vaporized by high-explosive projectiles [see figure 2]. This was industrial warfare on a grand scale that left men terrified, shrieking for help or for the artillery to simply stop. They were unable to escape the horror or to protect themselves other than by cowering at the bottom of what was left of a trench or dugout. The massive weight of Allied artillery fire was akin to a giant fist smashing down and was described by the Germans as “the week of suffering” (2–9 April 1917). One German soldier wrote of the experience: ”What the eyes see through the clouds of smoke is a sea of masses of earth thrown up and clouds of smoke rolling along…. How long did this nightmare last?”

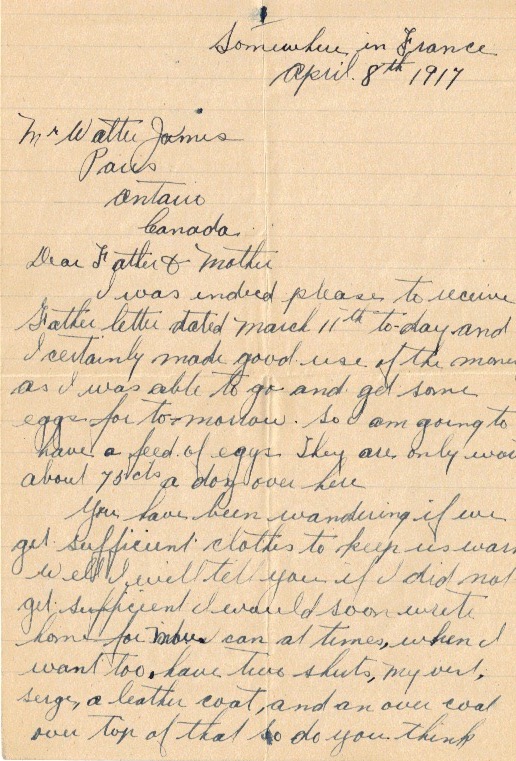

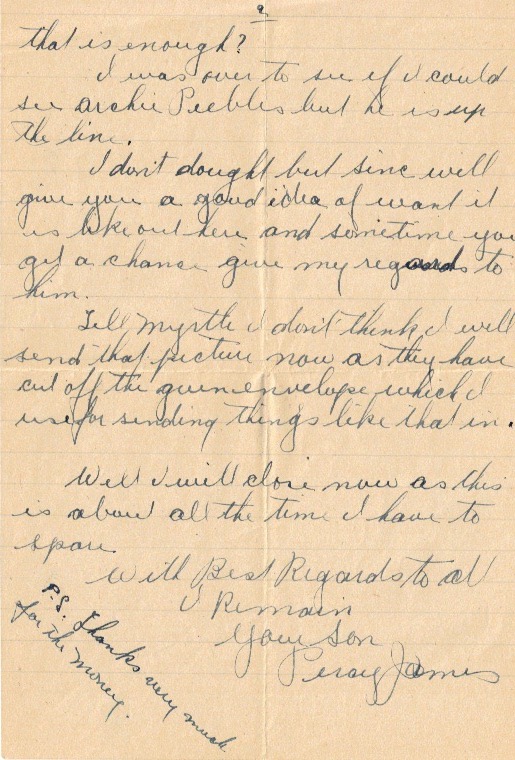

Meanwhile, within the ranks of the 19th Battalion, on both the 3rd and 8th of April 1917, L/Sgt Percy James sent letters home [see figure 3]. James maintains a typically breezy tone despite knowing the massive attack was coming soon. It is as if James anticipates this may be his last letter home and he characteristically wants to appear unconcerned and not wishing to upset his family. In an earlier letter on February 14th, he mentions entering the line from communication trenches and going into a cave. Perhaps he wanted to reassure his family of his safety. At that period, we know the 19th Bn was opposite the town of Thelus [see map 1], just west of Vimy Ridge, an area honeycombed with deep dugouts and tunnels designed to protect troops in preparation for the April attack.

Figure 3. L/Sgt Percy James’s letter home to his parents on the eve of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. The Argyll Museum and Archives contains all of his letters home during the war, 1914–1919.

Figure 3. L/Sgt Percy James’s letter home to his parents on the eve of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. The Argyll Museum and Archives contains all of his letters home during the war, 1914–1919.

Since the Commanding Officer, Lt-Col Millen, was away recuperating from bronchitis, the 19th continued training under the second in command, Maj Harry Hatch. Training was progressive in that they started at the platoon level, after which companies, the battalion, and finally the entire brigade conducted rehearsals over training courses that simulated the ground on which they would attack. Harry Neil of the 19th Bn thought the preparatory training “seemed unending.” Millen returned on 6 April and the battalion learned the attack was confirmed for 9 April. At the same time, Scouts from each company and the men of Numbers 1 and 3 Platoons were sent forward temporarily under command of the 20th Bn to improve their assembly areas for the attack. Concurrently, Maj Russell Thomson was given the task of surveying the German wire entanglements in front of the 19th Bn’s jumping-off points from an observation post in the ruins of Neuville-Saint-Vaast. He reported that all wire appeared to be well cut along the battalion’s front. From left to right: D, B and C Companies would advance three up with A company in depth and a portion of men from all four companies left out of battle as a follow-up reserve in the event of a catastrophe with the attacking troops. Each company was using newly developed platoon tactics, so they moved semi-independently in a diamond formation, allowing greater protection from German infantry and machine guns. The Canadian Corps had also integrated Lewis machine guns and rifle grenades into each platoon to increase firepower and coordinate fire with manoeuvre.

Map 1. The 19th Bn line of attack at Vimy. Courtesy of Dr. Mike Bechthold.

Map 1. The 19th Bn line of attack at Vimy. Courtesy of Dr. Mike Bechthold.

The men of the 19th assembled in their jumping-off trenches in the freezing pre-dawn morning of 9 April whilst sleet and snow fell over the windswept battlefield. Harry Neil remembered: “It was snowy and bitterly cold Easter Monday and the mud between our positions and the top of the Ridge had the consistency of glue.” [See figure 9 and look closely at the mud stuck to the legs of the troops consolidating their positions.]

The officers of the 19th Bn, like Maj Russell Thomson, “crawled up and down the trenches to wish us all good luck,” recalled Pte Art Clymer. Thomson was leading D Company in the attack, and as the Allies opened their final intense artillery barrage at 05:30 that morning, the Canadians hauled themselves up and over their trench parapets. Thomson was the first to go and was shot almost immediately. The 19th was temporarily held up by well-sighted German machine gun crews [see figures 12A, 12B, and 12C] that survived the barrage until mopping-up troops from the 20th Bn destroyed them with volleys of grenades. The effects of the creeping barrage and the destruction of their machine guns and crews left the remaining German troops without the will to resist, and so the Canadians pushed through their positions [see figure 10]. The 19th reported that by 06:07 all companies had reached their objectives along the Black Line [see map 1].

There were many heroes that day among the soldiers of the 19th Bn. Ed Youngman remembered one of them who was using the pseudonym Robertson. His real name was Fred Presnail and he came from a prominent Hamilton family. He had studied medicine before the war, but was disbarred from medical practice due to heavy medicinal drug use. Presnail came across a badly wounded soldier and “decided that this man should have his arm amputated, it was almost amputated anyway. He took the [straight] razor out of his pocket…he made a first-class job of finishing amputating that arm, and he sewed it up with thread from his ordinary kit, and the man was put on a stretcher and he went right on to casualty clearing.”

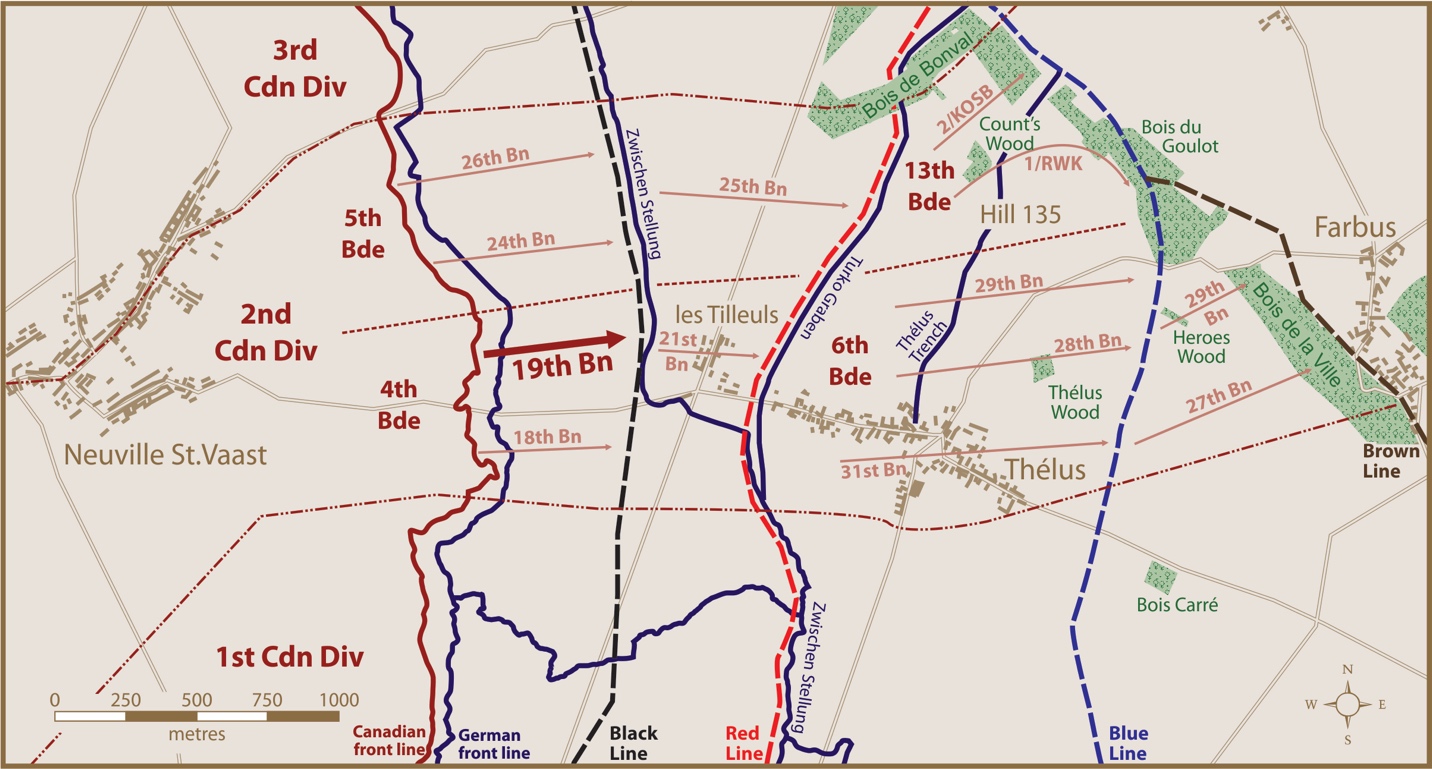

One of those killed at Vimy was LCol Walter W. Stewart, who prior to the war had been an architect and an officer in the 91st Highlanders. Stewart helped design the armouries on James Street in Hamilton and went overseas commanding the 86th Bn. He was later transferred to the Machine Gun Corps when the 86th was broken up for reinforcements. He was killed in action on the third day of the battle, 11 April 1917.

The 19th was part of the initial assault wave on the 9th of April, and after they had done magnificent work in seizing their objectives, the battle continued, with successive waves capturing the entire ridge and engaging in limited exploitation operations through to 14 April. Vimy was a great triumph and “…understood by those who were there as a significant victory.” Lt-Col Millen wrote home to his mother on 16 April to say, “You of course know we have been in a scrap. The whole thing was absolutely wonderful, everyone did fine.” Yes, the 19th had performed well, but at a cost. For the 19th Battalion, two officers were killed in action and one died later of wounds, while 32 other ranks also were killed. Six officers and 154 other ranks were wounded, and 27 other ranks were missing. A further 15 ranks were listed as sick. For the Canadian Corps, 9 April 1917 was the single bloodiest day of the war with 7,707 casualties. The Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9–14 April, cost Canada 10,602 casualties, 3,598 of them fatal.

Major Russell B. “Punk” Thomson, OC, D Coy, 19th Battalion (1888–1917)

This tribute was read during the 2013 Regimental Remembrance Day ceremony at the Argyll Commemorative Pavilion, Hamilton, Ont.:

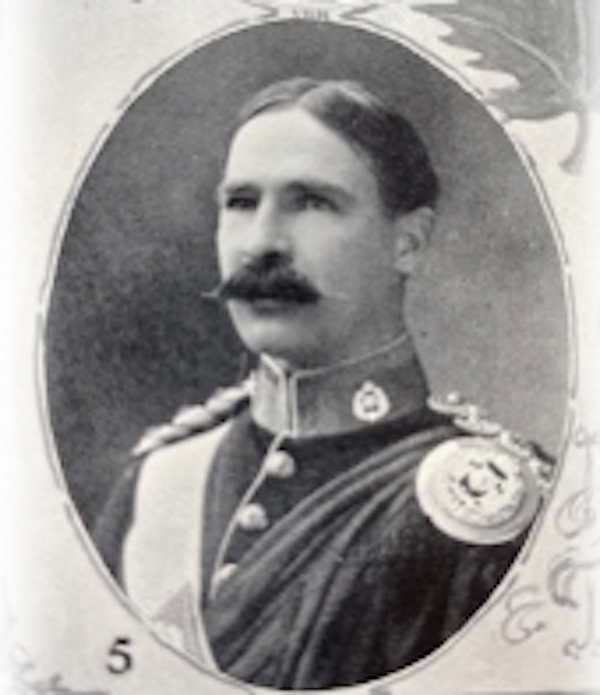

Tonight, we remember Russell Thomson, known to his brother officers as “Punk.” He joined the 91st Canadian Highlanders in the years before the First World War. Like many from the 91st, he joined the 19th Battalion, CEF, on the outbreak of war; in his case, it was 12 May 1915 and the officer signing him in was Maj Lionel Millen, later the battalion’s CO for most of the war. Punk Thomson was a Hamilton-born Canadian of a Scottish father. He was a salesman, a Presbyterian, and single. At 5’ 10½” with fair skin, blue eyes, and blonde hair, he was popular with officers and troops alike.

On 9 April 1917, the Canadian Corps, all four divisions, attacked Vimy Ridge. Thomson then commanded D Coy. In the early hours of the morning, he quietly moved up and down the line, offering a pat on the back, a handshake, and some final words of encouragement to his men. When the attack commenced, he was one of the first killed that day. Major D.E. Macintyre, the chief staff officer of the 4th Brigade, came across his body. He wrote:

“In No Man’s Land I recognized an officer of the 19th Battalion with whom I had enjoyed dinner a short time before the battle, and with whom I had played basketball in Canada. He lay in that awkward humpbacked posture I had so often observed in the dead, made more conspicuous by the heavy pack on his back as though the load had been too heavy and he had stumbled and fallen face down, his knees buckled under him, his hands spread before him. A gallant officer who died leading his men.”

Thomson had been a popular officer, and his death came as a sad blow for his friends in the battalion. “Poor Punk Thomson,” wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Millen, “I am glad he never knew what struck him. I went out myself with some other officers and found his body, and we were able to give him a proper burial in a regular cemetery.” At Vimy, the 19th had: 38 KIA, 154 wounded, and 27 missing. Thomson was among the dead; he is buried in the Ecoivres Military Cemetery, 1.5 km from Mont-Saint Eloi. Thomson left his battalion, his company, his parents, his friends, and his siblings to grieve. We shall remember him.

The German MG 08 Machine Gun

The images at right (figures 12A, 12B, 12C) show the remnants of a gun held by the Argyll Museum and Archives. It was captured during the battle for Vimy Ridge by the 19th Battalion. Unfortunately, it does not retain many of its original parts. Despite the crushing weight of Allied artillery fire, many well-dug-in machine gun positions survived, and it was this kind of machine gun that was holding up the advance of the 19th for a while on 9 April 1917, causing numerous casualties.

Specifications of a complete gun with tripod and water in the cooling jacket:

Weight total: 69 kg (152.1 lb) with water

Crew: 4

Cartridge: 7.92x57mm Mauser

Rate of fire: 450-500 rounds/min

Effective range: 2000 m (2187 yds)

Max range: 3700 m (4046 yds)

Feed system: 250 round fabric belt

Acknowledgments

A humble thank you to Dr. David Campbell for casting his professional historian’s eye over my draft work and his most welcome suggestions.

References & Credits

Special thanks to Dr. David Campbell and his history, It Can’t Last Forever: The 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War.

Dr. Mike Bechthold graciously provided the map and photos.

Tim Cook, Vimy: The Battle and the Legend

William F. Stewart, from Bombs, Bullets, and Bayonets: The Transformation of Canadian Infantry Firepower at Vimy Ridge

Mark Zuelke, Brave Battalion

Additional photos and letters from The Argyll Museum and Archives

Figure 1. The Canadian monument at Vimy, France, to the sacrifice of those who died during the battle and those throughout the war who have no known grave. Photo: Author’s collection.

Figure 1. The Canadian monument at Vimy, France, to the sacrifice of those who died during the battle and those throughout the war who have no known grave. Photo: Author’s collection.

Figure 2. Note the round ball shrapnel on the left, designed to airburst over enemy troops, and the jagged shards of projectiles on the right, shattered by the high explosive and used to cut wire entanglements. These artefacts are part of a display at the Argyll Museum and Archives.

Figure 2. Note the round ball shrapnel on the left, designed to airburst over enemy troops, and the jagged shards of projectiles on the right, shattered by the high explosive and used to cut wire entanglements. These artefacts are part of a display at the Argyll Museum and Archives.

Figure 4. The Commanding Officer, Lt-Col L. Millen, DSO and bar.

Figure 4. The Commanding Officer, Lt-Col L. Millen, DSO and bar.

Figure 5. The Second in Command, Maj H. Hatch, DSO.

Figure 5. The Second in Command, Maj H. Hatch, DSO.

Figure 6. Ground over which the 19th Bn advanced at Vimy, in the vicinity of their jumping-off line, on 9 April 1917. They would have advanced towards the hedge and trees on the horizon. From Dr. David Campbell’s collection.

Figure 6. Ground over which the 19th Bn advanced at Vimy, in the vicinity of their jumping-off line, on 9 April 1917. They would have advanced towards the hedge and trees on the horizon. From Dr. David Campbell’s collection.

Figure 7. Canadian infantry advancing through German wire entanglements on Vimy Ridge. Some of the explosions appear to be later additions to the original image. Such doctoring of photos was done for dramatic effect.

Figure 7. Canadian infantry advancing through German wire entanglements on Vimy Ridge. Some of the explosions appear to be later additions to the original image. Such doctoring of photos was done for dramatic effect.

Image 8. LCol Walter Stewart, KIA 11 April at Vimy.

Image 8. LCol Walter Stewart, KIA 11 April at Vimy.

Figure 9. Men of the 19th Bn consolidating their new positions on Vimy Ridge. The fighting had moved far enough ahead that a few men could take a brief break from their labours to pose for the camera.

Figure 9. Men of the 19th Bn consolidating their new positions on Vimy Ridge. The fighting had moved far enough ahead that a few men could take a brief break from their labours to pose for the camera.

Figure 10. Rounding up German prisoners.

Figure 10. Rounding up German prisoners.

Figure 11. Russell Thomson was a Lieutenant when this photo was taken and was later a Major commanding D Company when he was killed in action at Vimy.

Figure 11. Russell Thomson was a Lieutenant when this photo was taken and was later a Major commanding D Company when he was killed in action at Vimy.

Figure 12A. Remnants of the German MG 08 Machine Gun.

Figure 12A. Remnants of the German MG 08 Machine Gun.

Figure 12B.

Figure 12B.

Figure 12C.

Figure 12C.